LOOKING BACK - 125 YEARS AFTER THE TENNESSEE CENTENNIAL EXPOSITION

Digital Resources

Digital Books

Browse the books exhibited in Looking Back— 125 Years After the Exhibition

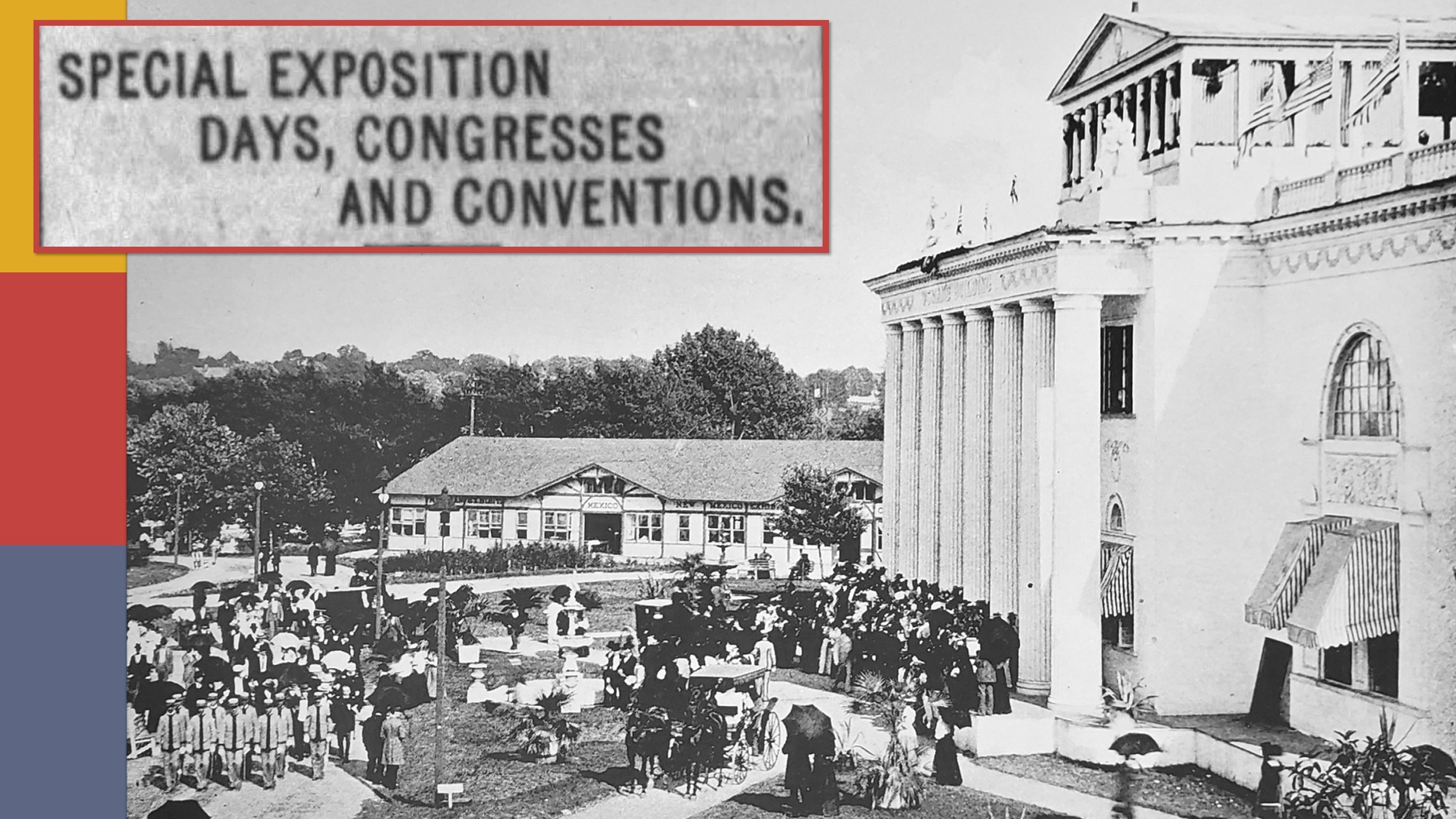

List of Special Days

What day would you want to visit the 1897 Tennessee Centennial Exposition? Browse the list of Special Days.

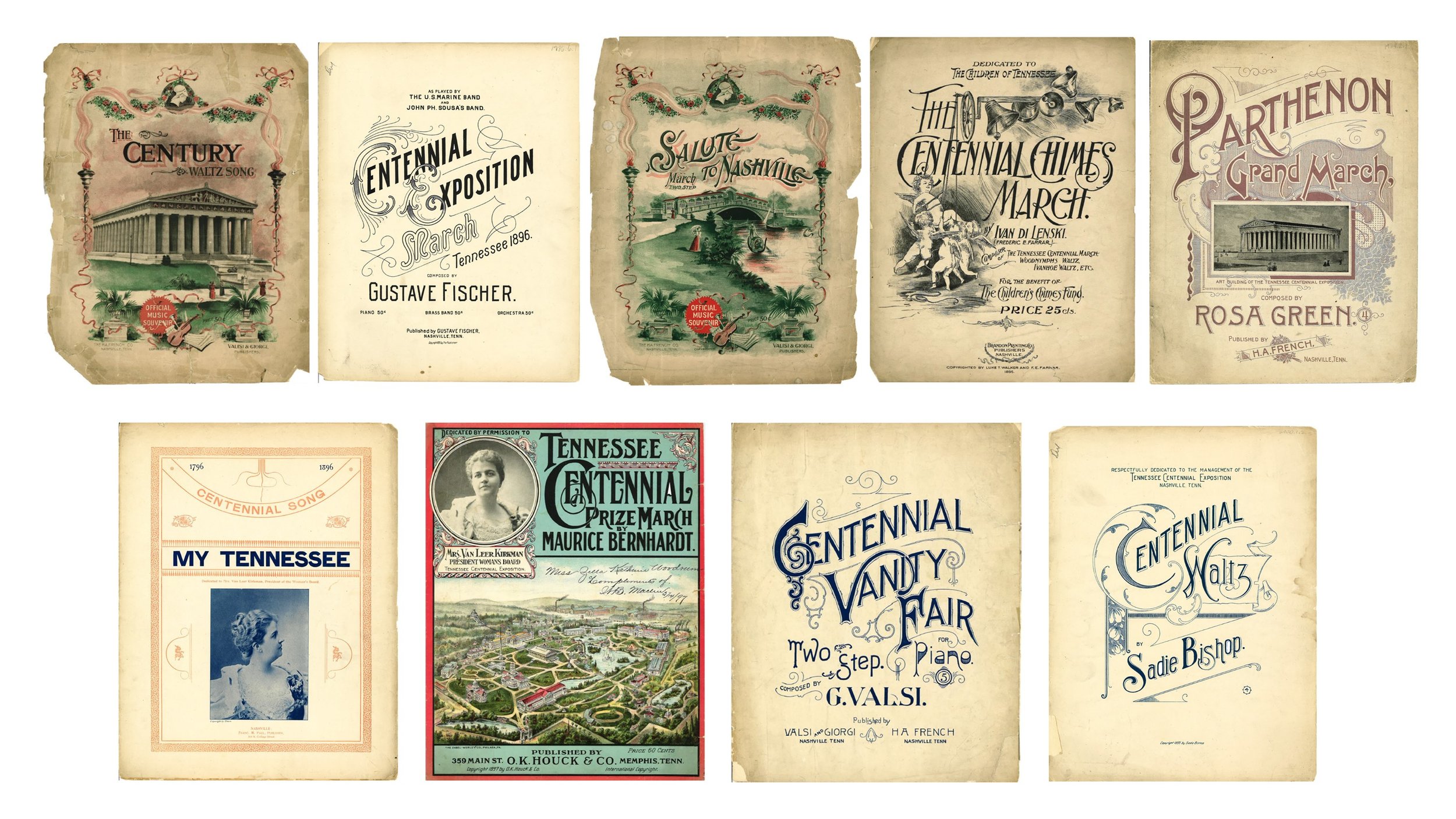

Sheet Music

Play music from the 1897 Tennessee Centennial Exposition at home! Browse the sheet music exhibited in Looking Back— 125 Years After the Exhibition:

SYMPOSIUM

Watch the Symposium from June 16, 2022, connected to the Tennessee Centennial Exposition. The recording is also available on YouTube.

Listen to the 1897 Tennessee Centennial Exposition

Enjoy these nine songs that filled the air with melody morning, noon, and night 125 years ago.

Special thanks to Centennial Performing Arts Studios for their assistance in bringing the sounds of 1897 to life.

The Negro Department of the Tennessee Centennial Exposition

Nestled in Centennial Park on the eastern bank of Lake Watauga, the Tennessee Centennial Exposition's Negro Building stood as a mark of Black achievement and as a weapon of white New South propaganda.

Designed by white architect Frederic Thompson, who would later co-design Coney Island's Luna Park, the 20,000 square foot two-story structure was Spanish Renaissance in design. It cost about $13,000 to construct and featured handsome towers, a red roof, a rooftop pavilion restaurant, and a medical facility with an all-Black staff to serve Black attendees.

The picturesque building stood as a striking monument to Black possibility. In the three decades since the Civil War, African Americans, despite the persistence of terroristic racism and white supremacy, had made great strides in many fields of endeavor. Black higher education was among the most remarkable of their achievements, and Nashville was home to three of the nation's most respected Black colleges, Fisk University, Central Tennessee College, and Roger Williams University.

Enshrined in Plessy v. Ferguson, segregation informed all interracial interactions, including planning the Tennessee Centennial Exposition. As New South boosters, the exposition's white planners viewed the Exposition as an opportunity to reassert white southern sovereignty over the region's race matters. Consequently, they were reluctant to allow the city's Black citizenry to display their achievements in a building of their own.

Unsurprisingly, Black planners had different ideas. Led by Nashville's most powerful and influential Black citizen, lawyer, and politician James Carroll Napier as Negro Department chief, they viewed a Negro Building as their chance to challenge white images of blackness. In protest, Napier's dissatisfaction led him to resign, claiming ill health, in August 1896.

Black schoolteacher Richard Hill succeeded Napier as Negro Department chief. White planners had viewed Hill as an accommodationist due to familial ties and dependence on a public salary. However, at the laying of the Negro Building's cornerstone on March 13, 1897, Hill stood before an overwhelming-Black crowd of 10,000, triumphant. He declared, "We are now on trial—the most severe test as to what we have done, and are doing, since our emancipation...We boast our enterprising spirit and progressivism. Our varied accomplishments have been proclaimed in flaming tones and painted in beautiful colors. Now is the time to prove all this."

The day's achievements did not belong alone to Hill. While the Exposition's Executive Committee was exclusively white, the Negro Department's leadership was owed to the city's leading Black citizens. Among the committee's members were the lawyer and three-time Republican member of the Tennessee General Assembly Samuel A. McElwee, businessman William T. Hightower, physicians William Abrums Hadley and Samuel A. Walker, school principal S. H. Sumner, and businessman and religious leader Preston Taylor. Added to them were the Negro Woman's Board members and an army of Black skilled and semi-skilled tradespeople who contributed to constructing the Exposition's buildings and infrastructure.

The Negro Building boasted over 300 exhibitors from 85 cities. Its diverse displays ranged from education and art to banking, technology, and science.

Celebration of its construction was widespread but not universal. Some Black Tennesseans called for a boycott of the Tennessee Centennial, but Hill and other enthusiasts focused on the Exposition's good. In addition to supposedly not being rabidly segregated, they touted the Exposition's calendar of special days for Black patrons. Negro Day, for example, drew more than 19,000 visitors, and others including Fisk University Day, Negro Employees Day, Central Tennessee College Day, Alumni Meharry College Day, National Race Council Day, Emancipation Day, and American Medical Association of Colored Physicians Day were leveraged as efforts to honor the "free, educated, aspiring new Negro."

When the Exposition closed on October 30, 1897, African Americans had won thirty-one certificates of commendation, three gold medals, five silver medals, and nineteen bronze medals. Today, the cornerstone of the Negro Building is on display in the John Hope and Aurelia E. Franklin Library at Fisk University.

— Crystal A. deGregory, Ph.D.

Flyover History

To celebrate the 125th anniversary of the 1897 Tennessee International Exposition, look through the lens of a modern-day drone, and see the Exposition magically come to life once again through the use of archival photographs.

Video: Carson Morton; Drone Pilot: Andrew Rozario